In English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI) contexts, students must simultaneously access new disciplinary knowledge and express their understanding using academic English. This dual challenge increases the cognitive and linguistic load placed on learners, especially when English is not their first language. Scaffolding academic language, therefore, becomes an essential instructional strategy to guide students in bridging the gap between conversational fluency and academic literacy.

Research shows that EMI can significantly enhance students’ academic language skills across various disciplines. For instance, studies indicate that EMI positively impacts writing proficiency, particularly in terms of lexical accuracy and vocabulary development, as demonstrated in engineering education contexts (Pérez, 2023). Additionally, structured models for academic writing in EMI settings emphasize awareness of academic genres and cross-cultural rhetorical patterns, which effectively scaffold students’ ability to produce discipline-appropriate written work (Gronchi, 2025).

Further research highlights the necessity of robust language support services and pedagogical approaches that promote interactive learning to address the challenges students face in EMI environments (Syahrudin & Sani, 2025). This supports the view that EMI policies should explicitly integrate English language development with subject learning, ensuring that content lecturers are equipped to assess and respond to language-related learning needs in their courses (Latif & Deen, 2024).

Such frameworks suggest that while EMI can enhance language acquisition and disciplinary learning, effective implementation requires systemic support structures—including teacher training, curriculum alignment, and classroom-level scaffolding—to maximize its educational benefits (Anggraini, 2023). In this sense, scaffolding academic language is not an optional addition to EMI, but a core pedagogical necessity for equitable and meaningful learning.

Why Scaffolding Matters in EMI Settings

Academic language is distinct from everyday language. It involves abstract vocabulary, complex sentence structures, hedging expressions, and discipline-specific terminology. In many Asian higher-education settings, students may understand content concepts but struggle to articulate them appropriately in English. Without support, participation becomes limited, confidence declines, and comprehension gaps widen.

Scaffolding ensures:

- Access to disciplinary meaning-making

- Development of critical thinking and academic reasoning

- Confidence in classroom discussions and assessments

- Enhanced long-term language proficiency

Types of Scaffolding Academic Language

1. Vocabulary Scaffolding

In EMI classes, students often encounter new terminology rapidly. Teachers can support learning by:

- Pre-teaching essential key terms before content exploration

- Using visuals, diagrams, and real-world examples to contextualize meaning

- Encouraging use of personal vocabulary journals for ongoing review

- Distinguishing between general academic words (e.g., “evaluate”) and discipline-specific terms (e.g., “morphosyntax”)

2. Sentence and Discourse Scaffolding

Students benefit when teachers model how academic ideas are structured in language. This may include:

- Providing sentence frames (e.g., “The data suggests that…”, “One implication of this is…”)

- Using graphic organizers to map argument structures

- Demonstrating how to reference sources and paraphrase effectively

3. Interactional Scaffolding

Classroom interaction plays a central role in the development of academic communication skills. Teachers can facilitate meaningful interaction through:

- Think-pair-share tasks before whole-class discussion

- Structured group roles (chair, recorder, presenter, questioner)

- Guiding questions that encourage elaboration, clarification, or justification

Integrating Scaffolding into Lesson Design

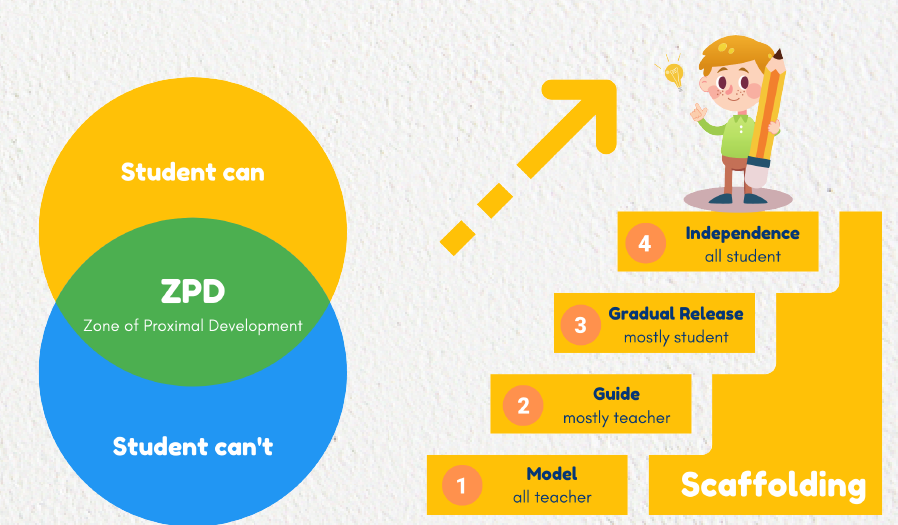

Effective scaffolding is deliberate and planned, rather than added as an afterthought. Teachers should anticipate linguistic difficulty in advance and embed language goals alongside content goals. A typical lesson may begin with activating background knowledge, introducing vocabulary, modeling disciplinary language, supporting guided practice, and gradually releasing responsibility to students for independent expression.

Moving Toward Autonomous Academic Communication

The ultimate goal of scaffolding is independence. When students internalize academic language structures, they are able to interpret scholarly texts, contribute to discussions, and produce research writing with increasing accuracy and sophistication. Teachers should gradually remove supports as students demonstrate readiness, while continuously offering formative feedback to refine clarity and precision.

Identify one disciplinary topic you teach. What academic vocabulary, sentence structures, or discussion strategies might students need support with? Design a short classroom activity that provides scaffolding for one of these areas.

References

Anggraini, Y. (2023). The use of English as a medium instruction in EFL classroom. Jurnal Smart, 9(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.52657/js.v9i2.2110

Gronchi, M. (2025). Making the implicit explicit: A structured learning pathway for academic writing in English medium instruction. SAJILE, 1(1), 2888. https://doi.org/10.15664/kvyryn44

Latif, M., & Deen, A. (2024). Whose responsibility? Saudi university EMI content teachers’ language-related assessment practices and beliefs. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03456-w

Pérez, M. (2023). The impact of EMI on student English writing proficiency in a Spanish undergraduate engineering context. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 13(2), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.38279

Syahrudin, N., & Sani, N. (2025). Perspectives of UniSZA students on English medium instruction (EMI) practices in higher education. E-Jurnal Penyelidikan Dan Inovasi, 12(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.53840/ejpi.v12i1.219